The first grape to arrive in the Americas

In Chile it is known as "País"; in Argentina, "Criolla"; and in California, "Mission". The vitis vinifera, which was the pioneer of viticulture in the Americas, came over from the Canary Islands in the 16h century and may now be making a comeback.

Long before Cabernet Sauvignon, Malbec, Pinot Noir and other "noble" varieties deployed their charms in the vineyards of the Americas, the Americas had other wines made from a grape variety which is far less well known, but which has the virtue of having been the first to cross the Atlantic. It significantly broadened the horizons of grape growing which, until that time, had been limited to the European “Old World”.

Little was known until recently about this red grape, whose strains had to adapt to some very different terroirs, from California in the north to the valleys stretching south of the subcontinent, alongside the Andes, in what is now Chile and Argentina. In each region where its cultivation developed this variety was renamed - Criolla (Argentina), País (Chile), Rosa del Peru (Peru) and Misión (Mexico) or Mission (California), and this undoubtedly hindered its identification and the tracing of its origins. There are those who even speculated about a probable Italian origin, but their theories were disproven when, in December 2007, a team of researchers from the National Centre for Biotechnology in Madrid, led by Alejandra Milla Tapia, solved the mystery, revealing that the grape at the origin of viticulture in the Americas, is Spanish. DNA samples taken from vineyards in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Peru and California were analysed, revealing that the genetics of the Criolla/ País / Mission are the same as the Listán Prieto, which is still grown in the Canary Islands today.

Little was known until recently about this red grape, whose strains had to adapt to some very different terroirs, from California in the north to the valleys stretching south of the subcontinent, alongside the Andes, in what is now Chile and Argentina. In each region where its cultivation developed this variety was renamed - Criolla (Argentina), País (Chile), Rosa del Peru (Peru) and Misión (Mexico) or Mission (California), and this undoubtedly hindered its identification and the tracing of its origins. There are those who even speculated about a probable Italian origin, but their theories were disproven when, in December 2007, a team of researchers from the National Centre for Biotechnology in Madrid, led by Alejandra Milla Tapia, solved the mystery, revealing that the grape at the origin of viticulture in the Americas, is Spanish. DNA samples taken from vineyards in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Peru and California were analysed, revealing that the genetics of the Criolla/ País / Mission are the same as the Listán Prieto, which is still grown in the Canary Islands today.

The rise and fall of the “missionary” grape

Chronicles of the colonization of the New World attest to the fact that Franciscan monks were responsible for introducing the Listán black grape to South America in the 16th century. Although they have not been able to determine whether the clones were picked up en route, when they stopped over on the islands, or transported directly from the Iberian Peninsula, where the variety also grew (especially in Castile, under the name of Palomino Negro).

Chronicles of the colonization of the New World attest to the fact that Franciscan monks were responsible for introducing the Listán black grape to South America in the 16th century. Although they have not been able to determine whether the clones were picked up en route, when they stopped over on the islands, or transported directly from the Iberian Peninsula, where the variety also grew (especially in Castile, under the name of Palomino Negro).

In any case, the "missionary" grape arrived in the viceroyalties of Peru and New Spain between 1520 and 1540. In South America, it found its best growing conditions in the south of what is now Chile and Argentina. Along with the white Muscat of Alexandria, the Criolla (or País) grape was the main protagonist of viticulture in these two countries until the second half of the 19th century, when varietals of French origin started to be introduced. This resulted in the Criolla being relegated to the poorest land with no other purpose than to produce ordinary table wines and mediocre bulk wine.

But as fate would have it, there is a new twist in the history of this pioneering black grape of viticulture in the Americas, if not yet a full blown comeback.

Chile: the sparkling country

Coronel of Maule, Torres Chile Despite having been sidelined, the País variety still accounts for around 15,000 hectares of vineyards in Chile, which makes it the second-most commonly planted variety, after the Cabernet Sauvignon. Nearly 8,000 grape growers are involved in its cultivation, mainly in the interior and coastal drylands of the Maule and Biobio Valleys.

Coronel of Maule, Torres Chile Despite having been sidelined, the País variety still accounts for around 15,000 hectares of vineyards in Chile, which makes it the second-most commonly planted variety, after the Cabernet Sauvignon. Nearly 8,000 grape growers are involved in its cultivation, mainly in the interior and coastal drylands of the Maule and Biobio Valleys.

The high acidity, the weak colouring potential and the low alcoholic strength of the País grape did not suit the purposes of the Chilean wineries which, from the 1980s, were scrambling to cater to the international demand for heavier, higher-alcohol and strongly-coloured red wines.

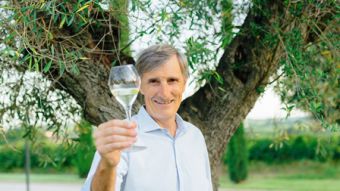

But now, with today’s demand for lighter, more acidic, and, if possible, authentic wines, the País’ luck seems to have changed. One of the first to give this variety another try was Spaniard, Miguel Torres Maczassek, who was at the reins of the Chilean branch of the family wine group before assuming the general management of the Miguel Torres Group.

Working in collaboration with the University of Talca, Torres rediscovered the potential of this variety thanks to studies that showed the way to producing an excellent sparkling wine using the Champenoise method. The result was Santa Digna Estelado, a sparkling rosé which has become the most highly rated Chilean sparkling wine by international critics today. After causing a stir with his Estelado, Torres has also illustrated the nobility of the País grape variety in a still red wine, Reserva de Pueblo. Here this variety shows finesse and fruity exuberance, along with a certain rusticity.

Torres is not, of course, the only producer who is putting the País grape variety to good use in Chile today. Another fine example of its potential is Huasa, from Clos Ouvert, in which Frenchman, Louis-Antoine Luyt, gives us his natural and honest take on this grape variety.

Argentina: The Criolla revolution

Matías Michelini, Argentina In Argentina, “Criolla” has suffered from a far greater marginalization in the last four decades than the “País” on the other side of the Andes: today it is not even in the Top 10 of the most planted red varieties, which is presided over by the Malbec, of course. This, however, has not put off a few experimental wine producers, who have in recent years vowed to restore Criolla’s nobility, bastardized by the table wines of the '60s.

Matías Michelini, Argentina In Argentina, “Criolla” has suffered from a far greater marginalization in the last four decades than the “País” on the other side of the Andes: today it is not even in the Top 10 of the most planted red varieties, which is presided over by the Malbec, of course. This, however, has not put off a few experimental wine producers, who have in recent years vowed to restore Criolla’s nobility, bastardized by the table wines of the '60s.

With uncommon lightness, that does not diminish its character, the Cara Sur Criolla red wine, put together by Sebastián Zuccardi and Francisco Bugallo in the Barreal vineyards in the San Juan valley of Calingasta, is one of the wines inviting us to take a closer look at the old Criolla vines. And it's not the only one: Within its Old Vines range, El Esteco presents a single varietal wine from this grape variety grown in the Cafayate heights (Salta). It comes from vines planted in 1958 at 1,800 metres altitude. And in the Valley of Uco in Mendoza, the iconoclastic Matías Michelini produces Vía Revolucionaria, another of the unique, new generation Criolla reds.

California: Mission impossible?

In California, the introduction of the Mission was later than in South America as it occurred in the 19th century. This was also due to Franciscan monks and their missionary work (hence the name). They grew the grape to produce their sacramental wines, but its use was soon expanded to the production of table wines and a traditional sweet fortified wine known as Angelica.

In California, the introduction of the Mission was later than in South America as it occurred in the 19th century. This was also due to Franciscan monks and their missionary work (hence the name). They grew the grape to produce their sacramental wines, but its use was soon expanded to the production of table wines and a traditional sweet fortified wine known as Angelica.

Sidelined after the arrival of other varietals, it is now hard to find any quality wines made from this grape variety in the most famous wine region of the U.S. Its presence is almost symbolic: only about 200 hectares of Mission vineyards survive in scattered plots and in Santa Barbara County in particular. But don’t be surprised if one of these days, the Californians turn up with an excellent wine that restores the missionary grape to its former glory.