The cellar in the sea

On 16 July 2010 an extraordinary treasure was discovered by a diving team just south of the Åland Archipelago, an autonomous region between Sweden and Finland: among the wreckage of a ship, which sank almost two centuries ago, were 168 bottles of champagne. 47 of these bottles turned out to be have been produced by Veuve Clicquot, and research has shown that they date back to between 1839 and 1841.

Bottles of Veuve Clicquot at the bottom of the Baltic SeaWhen the first champagne bottle from the wreckage was brought to the surface in July, it popped its cork due to the change in pressure during the ascent. The diving team tasted the contents and discovered that inside instead of seawater, there was a sweet wine, which had even retained some of its original fizz. This was astonishing, given that these bottles were almost 200 years old.

Bottles of Veuve Clicquot at the bottom of the Baltic SeaWhen the first champagne bottle from the wreckage was brought to the surface in July, it popped its cork due to the change in pressure during the ascent. The diving team tasted the contents and discovered that inside instead of seawater, there was a sweet wine, which had even retained some of its original fizz. This was astonishing, given that these bottles were almost 200 years old.

After a series of battles with the Russian Empire, Sweden ceded the Åland Archipelago as part of the Grand Duchy of Finland, to Russia. Then the Eastern gateway to the Russian Empire, the Archipelago was an important point of passage for ships bearing treasures to the lavish Russian Imperial Court, eager to indulge its taste for the finest luxuries. Thanks to the pioneering efforts of Madame Clicquot, who audaciously broke Napoleon’s trade embargo in 1814 and was the first to open Russian territory to the champagne trade, Veuve Clicquot champagnes were frequently part of the precious cargo that passed through the Baltic Sea.

Cave Prive Rrose 1979When the initial news of the Åland discovery circulated in 2010, it was not known which champagne house had produced the treasure trove. Veuve Clicquot, interested in learning more about the history of these old wines and eager to improve its knowledge of the champagne ageing process, volunteered its oenology expertise and technological support in order to bring the remaining bottles safely to the surface. The champagne house’s archive department helped authenticate and date the champagne. The recovery posed many challenges, requiring a new level of understanding of the resistance of glass and seals under pressure. Only when the mission was completed did Veuve Clicquot discover that 47 of their own bottles were among the stash.

Cave Prive Rrose 1979When the initial news of the Åland discovery circulated in 2010, it was not known which champagne house had produced the treasure trove. Veuve Clicquot, interested in learning more about the history of these old wines and eager to improve its knowledge of the champagne ageing process, volunteered its oenology expertise and technological support in order to bring the remaining bottles safely to the surface. The champagne house’s archive department helped authenticate and date the champagne. The recovery posed many challenges, requiring a new level of understanding of the resistance of glass and seals under pressure. Only when the mission was completed did Veuve Clicquot discover that 47 of their own bottles were among the stash.

In November 2010, ten of the bottles recovered from the shipwreck were opened and tasted by a gathering of connoisseurs and media in Maryam, the capital of Åland. They discovered that Veuve Clicquot’s champagnes were still drinkable and had suffered little damage due to the very high standards to which the wine had been made: the bottles themselves, their corks and seals, and the ageing performance of the wine inside.

A diving team about to lower bottles of Veuve Clicquot to the seabedIn line with 19th century taste preferences, this wine was sweeter than today’s champagnes. (In the past, champagne producers would add around 150 grams of sugar per litre compared to today’s formula, which calls for less than 10 g/l.). Despite the high sugar content, the experts’ verdict on the Veuve Clicquot champagne, which was opened that day, was that it was excellent: after strong aromas of “cheese” on the nose, the wine revealed some fruit and floral notes with many layers of complexity. The freshness was even more amazing for a wine of this age. Like the champagnes that Veuve Clicquot produces today, these very old vintages are testaments to the vision and high standards of Madame Clicquot herself. Her tireless efforts to improve and innovate shape Veuve Clicquot’s guiding philosophy today. Since the foundation of the champagne house in 1772, Veuve Clicquot champagnes have been produced with particular attention paid to their ageing potential and performance.

A diving team about to lower bottles of Veuve Clicquot to the seabedIn line with 19th century taste preferences, this wine was sweeter than today’s champagnes. (In the past, champagne producers would add around 150 grams of sugar per litre compared to today’s formula, which calls for less than 10 g/l.). Despite the high sugar content, the experts’ verdict on the Veuve Clicquot champagne, which was opened that day, was that it was excellent: after strong aromas of “cheese” on the nose, the wine revealed some fruit and floral notes with many layers of complexity. The freshness was even more amazing for a wine of this age. Like the champagnes that Veuve Clicquot produces today, these very old vintages are testaments to the vision and high standards of Madame Clicquot herself. Her tireless efforts to improve and innovate shape Veuve Clicquot’s guiding philosophy today. Since the foundation of the champagne house in 1772, Veuve Clicquot champagnes have been produced with particular attention paid to their ageing potential and performance.

Veuve Clicquot realized that part of the reason for the drinkability of these old champagnes was down to their accidental storage conditions. Three of the most important conditions for cellaring wine exist at the bottom of the sea: no light, a constant low temperature and a silent environment. Intrigued by the potential of harnessing nature, the champagne House built the “Åland Vault”, a container optimized for deep sea ageing; a testament to Veuve Clicquot’s ongoing commitment to better understanding the ageing process. But the Åland Vault is just the beginning…

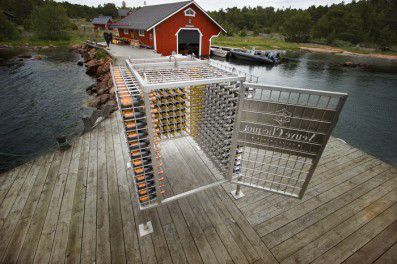

This is one of the locked crates in which they place the bottles of champagne before lowering them to the seabedThe bold experiment in ageing represented by the Åland Vault lies at the heart of Veuve Clicquot’s new Cellar in the Sea programme.

This is one of the locked crates in which they place the bottles of champagne before lowering them to the seabedThe bold experiment in ageing represented by the Åland Vault lies at the heart of Veuve Clicquot’s new Cellar in the Sea programme.

This daring initiative, symbolic of the champagne house’s ongoing commitment to innovation and excellence, is the start of a 50-year ageing experiment with controlled variables. A selection of non-vintage Yellow Label (in 75cl and magnum bottles), Vintage Rosé 2004 and demi-sec wines was placed inside the Åland Vault and sent 40 metres below the water’s surface , where their progress will be monitored by Veuve Clicquot cellar masters, who will also watch over duplicates of all the selected wines in the champagne house’s famous chalk cellars in Reims.

The complete collection of Veuve Clicquot’s Cave PrivéeThe Åland Vault has been submerged close to the site of the original shipwreck to attempt to recreate the same ageing environment. The Baltic Sea offers unique conditions with its poor salinity (20 times less than in the ocean) and a constant temperature of 4°C throughout the year. The submersion depth of 40 metres will prevent any seaweed attaching itself to the bottles to avoid the risk of an iodine taste appearing in the champagnes.

The complete collection of Veuve Clicquot’s Cave PrivéeThe Åland Vault has been submerged close to the site of the original shipwreck to attempt to recreate the same ageing environment. The Baltic Sea offers unique conditions with its poor salinity (20 times less than in the ocean) and a constant temperature of 4°C throughout the year. The submersion depth of 40 metres will prevent any seaweed attaching itself to the bottles to avoid the risk of an iodine taste appearing in the champagnes.

Seeking new ways to understand and innovate in the ageing process, Veuve Clicquot plans to retrieve some wines from the sea on a regular basis and conduct comparative tastings with the duplicate bottles from the cellars in Reims in the presence of a panel of professional tasters. In addition, samples of the retrieved wines will be sent to the oenological universities of Reims and Bordeaux to undergo technical analyses to discover the ageing secrets of the Baltic Sea.

Wooden gift box Cave Privée white 1989The first bottles destined for the Cellar in the Sea were submerged on 18 June, 2014. To celebrate the Summer Solstice, the one day of the year when the sun never sets on Åland, Veuve Clicquot launched a second offer of their Cave Privée, on Silverskär Island. This selection of vintages, all over 20 years of age, has been carefully crafted and aged in the best conditions by Veuve Clicquot’s long line of cellar masters in Reims.

Wooden gift box Cave Privée white 1989The first bottles destined for the Cellar in the Sea were submerged on 18 June, 2014. To celebrate the Summer Solstice, the one day of the year when the sun never sets on Åland, Veuve Clicquot launched a second offer of their Cave Privée, on Silverskär Island. This selection of vintages, all over 20 years of age, has been carefully crafted and aged in the best conditions by Veuve Clicquot’s long line of cellar masters in Reims.