The best Single Estates of the Single Estate Wines

This is not a play on words, despite seeming so. The use of the expression “pago” in the oenological field encompasses so many meanings that it becomes difficult to convey any sort of clarity to the end consumer. Singling out the best, we attempt to shed some light on these concepts.

If there wasn’t enough confusion already surrounding the term “pago”, which is roughly equivalent to the French “Cru”, in other words a specific parcel with certain characteristics that distinguish it from the rest, the creation a few years ago of the new category Vino de Pago Denomination of Origin has complicated matters further and wine enthusiasts can’t make head nor tail of this expression.

For a start, you can find wines belonging to the ‘Grandes Pagos de España’ (Great Single Estates of Spain); then again, a great many wines are called Pago de... los Capellanes, de la Sonsierra, de Larrainzar, de Carraovejas, del Ama, del Amón, del Espino, de Tharsys, del Moncayo, Vilches…. And so on up to at least 80 brand names. (Ever since the Vino de Pago DO became officially recognised, wineries have no longer been allowed to register as a brand the term Pago de... although brands already in existence before then remain.) Lastly, and for some years now, there are wines that have the official Vino de Pago Denomination of Origin. Three different concepts for the same single expression.

Vineyards at Bodegas MartúeI always say that our Spanish language which is so rich, cultured and beautiful for poetry and prose, for poets and writers, appears very stingy in the field of oenology. And above all, unclear, since it uses far too often and with different meanings the terms “pago”, “reserva”, “gran reserva” and “crianza”. Turning Reserva, Gran Reserva and Crianza into official terms for certain wine categories, with specified conditional factors, is tantamount to creating a lot of confusion, especially for foreigners, who do not understand why, of the same vintage, there is a Reserva, Crianza, Gran Reserva... It’s a subject offering enough material for a Spanish Language Conference on Oenology Terminology Usage... but let us return to Single Estate Wines which have brought us thus far.

Vineyards at Bodegas MartúeI always say that our Spanish language which is so rich, cultured and beautiful for poetry and prose, for poets and writers, appears very stingy in the field of oenology. And above all, unclear, since it uses far too often and with different meanings the terms “pago”, “reserva”, “gran reserva” and “crianza”. Turning Reserva, Gran Reserva and Crianza into official terms for certain wine categories, with specified conditional factors, is tantamount to creating a lot of confusion, especially for foreigners, who do not understand why, of the same vintage, there is a Reserva, Crianza, Gran Reserva... It’s a subject offering enough material for a Spanish Language Conference on Oenology Terminology Usage... but let us return to Single Estate Wines which have brought us thus far.

Vino de Pago Denomination of Origin

Vineyards at Bodegas MartúeWhat officially is a wine with the Vino de Pago DO? According to the Vineyard and Wine Law of 2003, Vino de Pago (Wine of a Single Estate or Vineyard) is a Protected Denomination of Origin, which for the present is only recognised by this name in the following Autonomous Communities: Navarra, Castile-La Mancha, Valencia and Aragon. In Rioja, Ribera del Duero, Rueda, El Bierzo, Toro…. there are presently no wines with this official classification. That’s why you won’t find a Vino de Pago in the regions of the Ribera del Duero, or Rioja, or Jerez...

Vineyards at Bodegas MartúeWhat officially is a wine with the Vino de Pago DO? According to the Vineyard and Wine Law of 2003, Vino de Pago (Wine of a Single Estate or Vineyard) is a Protected Denomination of Origin, which for the present is only recognised by this name in the following Autonomous Communities: Navarra, Castile-La Mancha, Valencia and Aragon. In Rioja, Ribera del Duero, Rueda, El Bierzo, Toro…. there are presently no wines with this official classification. That’s why you won’t find a Vino de Pago in the regions of the Ribera del Duero, or Rioja, or Jerez...

Therefore, it is both justifiable and essential to make the point that, although the new Vino de Pago DO takes in top quality bodegas and wines, it doesn’t mean they are better than many of the wines that don’t have this classification. For example, the very prestigious wines of long-standing in our country, those of Vega Sicilia, are not officially titled ‘Vino de Pago’; neither are the mythical Pingus, nor the great, traditional Riojas.

Wines that come under the Vino de Pago DO have to originate from grapes grown in a specific rural location or place whose name has been in use for at least 5 years, although not in an official manner. Effectively, it means that the local people have come to know the area or parcel by that particular name, Pago de Such and Such, and the grape-growing, wine-making and bottling will have to be carried out within the “pago”. In addition, for a winery to succeed in obtaining the Vino de Pago DO status, its wines need to have enjoyed continued success over the previous 10 years, and must have received recognition from consumers, restaurants, the best guides and specialist press which – as you can see now, and about time too – seems to stand for something.

Wines that come under the Vino de Pago DO have to originate from grapes grown in a specific rural location or place whose name has been in use for at least 5 years, although not in an official manner. Effectively, it means that the local people have come to know the area or parcel by that particular name, Pago de Such and Such, and the grape-growing, wine-making and bottling will have to be carried out within the “pago”. In addition, for a winery to succeed in obtaining the Vino de Pago DO status, its wines need to have enjoyed continued success over the previous 10 years, and must have received recognition from consumers, restaurants, the best guides and specialist press which – as you can see now, and about time too – seems to stand for something.

In short, you can say that the Vino de Pago DO is equivalent to a Denomination of Individual Origin, and take it for granted that the wines must be of excellent quality, since there are so many requirements for achieving this classification. The wineries can only vinify their own grapes and the winery itself must be situated within the “pago”. It is important to point out that this DO takes in the wine, but not necessarily the winery. That is to say, there are wineries which according to the law make Vinos de Pago or Single Estate Wines, as is the case with Bodega Otazu in Navarra, but only one of the wines that they make is presently acknowledged as Vino de Pago, namely the Pago de Otazu DO. This also happens in the case of Bodegas Mustiguillo, the first Vino de Pago DO in the Valencia region, recognised in September 2010, and of the three wines they make, only two come under the category of Vino de Pago DO, leaving the third outside for the moment.

Carlos Falcó and his daughter Xandra. (Valdepusa)According to the wording of the law, it might be the case that the Pago is very limited in size, as happens in France, where you find that wines of great historical prestige have a vineyard hardly exceeding a hectare. This occurs at Romanée-Conti and La Tâche, with neither of them amounting to two-hectare vineyards... In such a small “pago” there is no space to build a winery. As you can appreciate, nobody is going to pull up the vines of such a tiny parcel and fantastic quality in order to put up a building. The wineries are nearby but not inside the “pago”... Hold on!!! Now these could never have Vino de Pago status, and we must remember these Denominations are by nature European. It’s not some Spanish whim. So how paradoxical and contradictory laws can be!!

Carlos Falcó and his daughter Xandra. (Valdepusa)According to the wording of the law, it might be the case that the Pago is very limited in size, as happens in France, where you find that wines of great historical prestige have a vineyard hardly exceeding a hectare. This occurs at Romanée-Conti and La Tâche, with neither of them amounting to two-hectare vineyards... In such a small “pago” there is no space to build a winery. As you can appreciate, nobody is going to pull up the vines of such a tiny parcel and fantastic quality in order to put up a building. The wineries are nearby but not inside the “pago”... Hold on!!! Now these could never have Vino de Pago status, and we must remember these Denominations are by nature European. It’s not some Spanish whim. So how paradoxical and contradictory laws can be!!

For some years now there has been this expression: Grandes Pagos de España.

Twenty-five wineries from different areas have formed an association with this name and with the aim of promoting themselves as a group. There can be no doubt that there is strength in numbers and it’s absolutely commendable, but the name does contribute to a certain amount of confusion. The great driving force behind this association is Carlos Falcó, the Marquis of Griñón, who in his own right has a veritable Vino de Pago DO for his Malpico de Tajo wines, which is specifically known as the Dominio de Valdepusa DO. Among the 25 wineries that make up the association, there are five others that have been recognised in their own right with Vino de Pago Denomination of Origin. These are the Bodega Propiedad de Arínzano (Arínzano inca Élez DO).

Monumental Single Estates

Mansion on the Otazu estateAmong the twelve Vino de Pago DOs that have currently been recognised in our country, there are two that have certain very distinctive features which make them of special interest as regards wine tourism and architecture. They are the Arínzano DO and Otazu DO, two Navarran manors. Arinzano is a beautiful estate, located near Estella, belonging to the Chivite family, in a lovely countryside location and a fine example of environmental sustainability thanks to an agreement signed with the WWF in the 1990s. A valley in the final foothills of the Pyrenees, divided by the winding waters of the River Ega. The exclusive micro-climates create a remarkable environment for growing vines. Of the 355 hectares of land, 128 are used for cultivating the Pago vineyards.

Mansion on the Otazu estateAmong the twelve Vino de Pago DOs that have currently been recognised in our country, there are two that have certain very distinctive features which make them of special interest as regards wine tourism and architecture. They are the Arínzano DO and Otazu DO, two Navarran manors. Arinzano is a beautiful estate, located near Estella, belonging to the Chivite family, in a lovely countryside location and a fine example of environmental sustainability thanks to an agreement signed with the WWF in the 1990s. A valley in the final foothills of the Pyrenees, divided by the winding waters of the River Ega. The exclusive micro-climates create a remarkable environment for growing vines. Of the 355 hectares of land, 128 are used for cultivating the Pago vineyards.

The Señorío de Arínzano has been well-known for its excellent vineyards since the 11th Century, when the lord of the manor, Sancho Fortuñones de Arínzano, made wines on the estate for the first time. After successive owners, the property was virtually left abandoned until 1998, when the Chivite family rediscovered it and the great architect Rafael Moneo built a completely new, outstanding winery and renovated the old buildings, creating a very attractive complex. Its only wine under the Arinzano brand is an exceptional, elegant blend of Tempranillo and Merlot, with around 14 months spent in the finest quality French oak barrels.

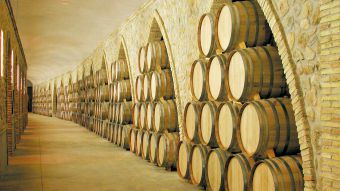

House at ValdepusaBeauty radiates too from all four points points of the compass at Otazu, just outside Pamplona, between the Perdón and Echauri mountain ranges. This is a historic manor dating back to the Middle Ages, where wine was already being made in the 12th Century. A set of architectural monuments in a spectacular spot, which brings together both a Romanesque church and a 16th Century Renaissance mansion, a 14th Century defence tower, a 19th Century wine cellar and a spectacular, ultra-modern winery, from the 21st Century. A magical place, full of history and art, since its owners are great collectors and sculptures crafted by the great artist Manolo Valdés are exhibited among the barrels of its impressive bodega. Its Señorío de Otazu wine, a red with 18 months in French barrels, made from Cabernet Sauvignon and Tempranillo, is the winery’s only one so far that can boast this distinguished designation.

House at ValdepusaBeauty radiates too from all four points points of the compass at Otazu, just outside Pamplona, between the Perdón and Echauri mountain ranges. This is a historic manor dating back to the Middle Ages, where wine was already being made in the 12th Century. A set of architectural monuments in a spectacular spot, which brings together both a Romanesque church and a 16th Century Renaissance mansion, a 14th Century defence tower, a 19th Century wine cellar and a spectacular, ultra-modern winery, from the 21st Century. A magical place, full of history and art, since its owners are great collectors and sculptures crafted by the great artist Manolo Valdés are exhibited among the barrels of its impressive bodega. Its Señorío de Otazu wine, a red with 18 months in French barrels, made from Cabernet Sauvignon and Tempranillo, is the winery’s only one so far that can boast this distinguished designation.

Exceptional Single Estates

Vineyards at ValdepusaLeaving Navarra we make our way to the lands of Valencia, near Utiel, to the unique Vino de Pago El Terrerazo DO, which Bodegas Mustiguillo holds for two of its wines, El Terrerazo and Quincha Corral. Located on the Mediterranean high plateau at an altitude of 850 metres, some 100 kilometres from the sea and near Teruel, it boasts old, unirrigated bush vines, many of which were planted in the 1940s. This is the family-run project of oenologist Toni Sarrión, which has continued to achieve great success ever since its beginnings in 1998. Wines of great personality and different from the rest, the result of Toni’s endeavours in taking the Bobal grape variety out of its downgraded, inferior category and, until his initiative got under way, used for bulk wine and the like, for some cheapish rosé. It is an estate where Kermes oaks, rosemary and thyme bushes, pines, almond and olive trees live peaceably alongside the grapevines, always grown organically. A fine example to follow. His wines, Finca Terrerazo and Quincha Corral, provide the best and most elegant expression of the Bobal grape, widely acknowledged as two of the Valencian Community’s finest wines.

Vineyards at ValdepusaLeaving Navarra we make our way to the lands of Valencia, near Utiel, to the unique Vino de Pago El Terrerazo DO, which Bodegas Mustiguillo holds for two of its wines, El Terrerazo and Quincha Corral. Located on the Mediterranean high plateau at an altitude of 850 metres, some 100 kilometres from the sea and near Teruel, it boasts old, unirrigated bush vines, many of which were planted in the 1940s. This is the family-run project of oenologist Toni Sarrión, which has continued to achieve great success ever since its beginnings in 1998. Wines of great personality and different from the rest, the result of Toni’s endeavours in taking the Bobal grape variety out of its downgraded, inferior category and, until his initiative got under way, used for bulk wine and the like, for some cheapish rosé. It is an estate where Kermes oaks, rosemary and thyme bushes, pines, almond and olive trees live peaceably alongside the grapevines, always grown organically. A fine example to follow. His wines, Finca Terrerazo and Quincha Corral, provide the best and most elegant expression of the Bobal grape, widely acknowledged as two of the Valencian Community’s finest wines.

Another endeavour, this time to bring out the best of lands in La Mancha, also quite unknown historically as capable of producing fine wines, is that of Carlos Falcó, Marquis of Griñón, notably prestigious in social and wine-growing circles, one of the pioneers in the modernisation of Spanish viticulture, and especially over in the Toledo region, near Malpica de Tajo, where his family have owned estates since the 13th Century. He was granted the first Vino de Pago DO for all his wines, which now proudly boast the Dominio de Valdepusa DO trademark, and was the first to introduce French grapevines into the La Mancha region forty years ago. Carlos Falcó, apart from being a well-known public figure, is a qualified agricultural engineer educated at top universities in the USA and France.

Old vine-stock at Finca TerrerazoIn nearby Ciudad Real too, there is another Vino de Pago of high standing, quality and merit. This time it bears the name of its owner, Florentino Arzuaga, and the DO is called Pago Florentino. A well-known winemaker in the Ribera del Duero, he made the move to the La Mancha region, due to a liking for Cornicabra olive trees. He bought 150 ha to make “Premium” olive oil and discovered in passing an exceptional “terroir” for making top quality wines too, always using the Tempranillo variety, known locally as Cencibel. His limited production wine, Pago Florentino, is a very good example. Florentino is also the father of our most internationally famous designer, Amaya Arzuaga.

Old vine-stock at Finca TerrerazoIn nearby Ciudad Real too, there is another Vino de Pago of high standing, quality and merit. This time it bears the name of its owner, Florentino Arzuaga, and the DO is called Pago Florentino. A well-known winemaker in the Ribera del Duero, he made the move to the La Mancha region, due to a liking for Cornicabra olive trees. He bought 150 ha to make “Premium” olive oil and discovered in passing an exceptional “terroir” for making top quality wines too, always using the Tempranillo variety, known locally as Cencibel. His limited production wine, Pago Florentino, is a very good example. Florentino is also the father of our most internationally famous designer, Amaya Arzuaga.