Old vineyards and old wineries in Victoria

Mount Edelstone

Mount Edelstone

There are some ideas that, no matter how entrenched they are, do not stand up to reality. One of these is the conviction that old vineyards and traditional old wineries are the exclusive preserve of European countries. Many people in Europe associate the New World with ultra-modern, highly productive vineyards and hi-tech wineries, associating the charm of time worn wood and mysterious old wineries whose cobwebs have seen hundreds of vintages, with the old world.

A neat thought in its simplicity but wrong, I’m afraid. The vast majority of European vineyards are very young, and they struggle to attain old age. In my opinion, there are two major historical reasons for this.

Firstly, in the period between 1860-1910, the European vineyards suffered from a series of the most destructive plagues ever to hit any plant species. Powdery mildew, downy mildew and phylloxera arrived from the U.S. in almost fatal succession. Our species of vine survived but paid a high price. On the one hand, the use of sulphur and copper on plants and soil became widespread, which is not good for the long-term vitality of [1] either, and on the other hand, almost all of our vines are now grafted on American rootstock [2]. Although I find no scientific basis to prove it, and so please accept my mea culpa in advance if I'm wrong, but I have the impression that grafted plants are unable to survive for centuries in the same way as ungrafted vines are.

The second reason for them failing to attain old age is competitiveness. We live in an age where it is seen as important not to be merely “good” but to be “better” than the others, because these days it's all about competing. Even in our vineyards. From old vines planted in poor soils where nothing else can grow, to today's vines whose yields in kilos per hectare have multiplied tenfold. To achieve this, we dope our vineyards with mineral fertilizers, pesticides and irrigation water in abundance while we can, aiming for high yields. Not content with this, we select clones [3]which are highly productive, we plant a single clone and are disinterested in biodiversity. After all, if we have the best, why do we need the others?

At best, the price to pay for such competitiveness is wines that do not represent their terroir because the grapes come from a doped, grafted clone vine growing in lifeless soil. The vineyard itself dies worn out and rotten at the age 35, despite the fact that there are numerous mentions of century-old vineyards around the world throughout history. In fact, due to its creeper nature, the vine should live for many centuries.

When I talk about this, many friends tell me that they cannot differentiate between a young or old vine, or an organic or non organic wine in tastings. And often I don't either, which is proof of our limited tasting ability. But, although my poor senses are unable to distinguish it, common sense tells me that if you give me a wine from an old vineyard, which is neither treated nor doped, my body and my soul will thank you for it.

We still have lots of old vineyards in Europe, The 1850 vineyards in Cour-Cheverny spring to mind, some centuries old vineyards on the Amalfi Coast or in the "vinho verde" region in Portugal, some Garnacha in Navarra enjoyed by Alfonso XII ....But most of what we sell as "old vines" are wines from vineyards which are less than 60 years old, and often, even 40 years old:: infants. It reminds me of when people died at 40 in the Middle Ages and someone aged 32 was referred to as old.

We still have lots of old vineyards in Europe, The 1850 vineyards in Cour-Cheverny spring to mind, some centuries old vineyards on the Amalfi Coast or in the "vinho verde" region in Portugal, some Garnacha in Navarra enjoyed by Alfonso XII ....But most of what we sell as "old vines" are wines from vineyards which are less than 60 years old, and often, even 40 years old:: infants. It reminds me of when people died at 40 in the Middle Ages and someone aged 32 was referred to as old.

You have to travel a long way to see an abundance of old vines. Today, Australia and Chile are home to a priceless wine heritage of pre-phylloxera, ungrafted vines. It is odd that it is in countries where governments are less interventionist and less vocal in the defence of tradition, where most heritage actually remains.

There are lots to choose from. I'll cite a few names in Australia, but leave Chile and its magnificent Cariñenas and Cabernets in Curicó for another time. Best's in Great Western, Victoria, planted its 22 hectare vineyard in 1866, with everything that they salvaged from the nurseries, many years later it was discovered that there are 39 different grape varieties, some still unidentified. Each wine is a wonderful living museum. I recommend the white Concongella, a delicate wine of only 11.5° alcohol, from vineyards which are over 140 years old, as we have the young vines to give much ethanol. Its star wines are the Shiraz wines, especially the White Gravels Hill and the iconic Thomson Family Block. Both deliver extraordinary sensuality and drinkability, and bear no resemblance to the monsters of fruit and tannin well known from these parts.

There are lots to choose from. I'll cite a few names in Australia, but leave Chile and its magnificent Cariñenas and Cabernets in Curicó for another time. Best's in Great Western, Victoria, planted its 22 hectare vineyard in 1866, with everything that they salvaged from the nurseries, many years later it was discovered that there are 39 different grape varieties, some still unidentified. Each wine is a wonderful living museum. I recommend the white Concongella, a delicate wine of only 11.5° alcohol, from vineyards which are over 140 years old, as we have the young vines to give much ethanol. Its star wines are the Shiraz wines, especially the White Gravels Hill and the iconic Thomson Family Block. Both deliver extraordinary sensuality and drinkability, and bear no resemblance to the monsters of fruit and tannin well known from these parts.

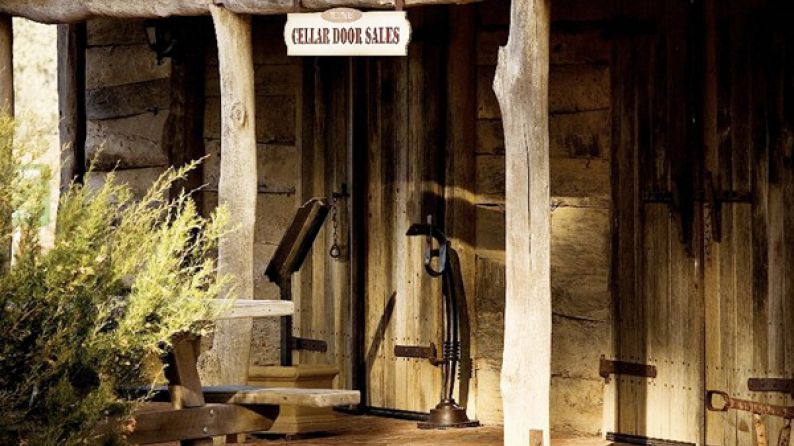

Tahbilk, in Nagambie Lake, Victoria, was established six years before Best's, with vines still in production, and a lovely winery still used today. Their "1860 vines" Shiraz wines are gems of balance and personality and need time in bottle to express themselves to the full. Right now, their 1996 is my favourite. The younger Marsanne vines planted in 1927 produce an original, silky white wine with beautiful minerality, for laying down. The 2000 is ready to drink now.

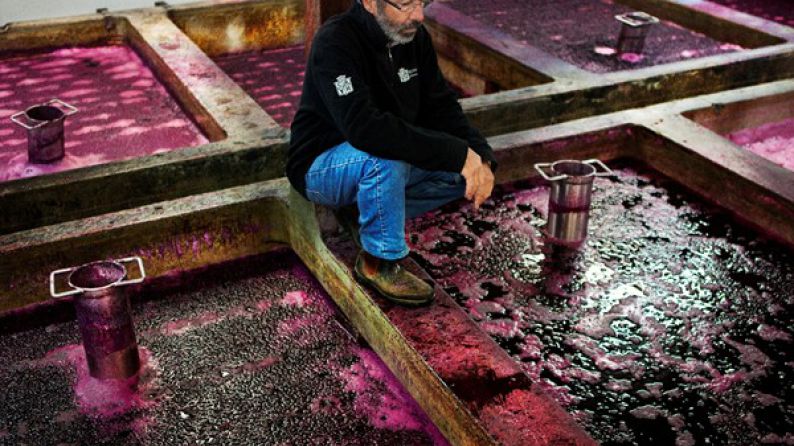

D'Arenberg - Compacting skins in basket press after fermentation and prior to basket pressingRutherglen is one of those little known regions which have a fascinating history and unique personality. The region was "invented" to quench the thirst of miners during the gold rush in the late nineteenth century. Once the gold ran out, it appears the region remained in the ether, producing wines outside of time and fashion. These are fortified Muscats with a large amount of residual sugar, so much in some cases that I doubt fermentation of the must was even possible [4], so I think in actual fact it is not wine they make but mistela. They age their wines using the solera system invented by the bodegas of Jerez, or rather with slightly anarchic versions of this. The result is delicious wines in which we feel a Mediterranean style of gentle oxidation and an intense finish with an exuberant touch and sweet profusion, unique to the extroverted Australian character. My favourites are the Isabella Rare Topaque from Campbell (classical, complex, long) and the Grand Rutherglen Topaque from All Saints (more immediate, very moscatel style, baroque).

D'Arenberg - Compacting skins in basket press after fermentation and prior to basket pressingRutherglen is one of those little known regions which have a fascinating history and unique personality. The region was "invented" to quench the thirst of miners during the gold rush in the late nineteenth century. Once the gold ran out, it appears the region remained in the ether, producing wines outside of time and fashion. These are fortified Muscats with a large amount of residual sugar, so much in some cases that I doubt fermentation of the must was even possible [4], so I think in actual fact it is not wine they make but mistela. They age their wines using the solera system invented by the bodegas of Jerez, or rather with slightly anarchic versions of this. The result is delicious wines in which we feel a Mediterranean style of gentle oxidation and an intense finish with an exuberant touch and sweet profusion, unique to the extroverted Australian character. My favourites are the Isabella Rare Topaque from Campbell (classical, complex, long) and the Grand Rutherglen Topaque from All Saints (more immediate, very moscatel style, baroque).

I have left out many, too many, great Australian winemakers who offer us the wonderful produce of vineyards and wineries which have benefitted from over a century of uninterrupted activity. Some are mythical such as Henschke, references such as Penfold's or exciting like D'Arenberg. Due to lack of space here, I can only recommend you to try these wines. To be able to enjoy the magic of truly old vines, the blood, sweat and tears of several generations who shared the same dreams, cherished what they had inherited and passed it on to those who came after them, is already an experience. Only wine lets you drink history. Just one of the many reasons which make it great.

[1] Powdery mildew is treated with mineral sulphur and powdery mildew with copper sulfate. Both substances are moderately toxic to the plant and the microbial life of the soil

[2] Phylloxera feeds on the tender roots of the vine. The European vine, Vitis vinifera, cannot heal the wounds in the root, so remains exposed to diseases and dies quickly, while the American species heals quickly and can therefore live with the pest. Hence the European buds are grafted on American plants without buds, so that the American plant develops the roots below ground which feed the European part of the vine above ground. When tasted, there are no discernable differences between grafted wines and ungrafted wines, which does not, of course, mean that there aren't any.

[3] The commercial vine multiplies vegetatively, not by seeds. A clone is a single individual, from which stakes are multiplied, each stake creates a new vine.

[4] When there is a lot of sugar in a liquid, the sugar concentration creates so much osmotic pressure that the yeast cannot live in the environment.