Let’s save Sherry

As a lover of Spanish, nothing hurts me more than the contempt that wines from the Marco de Jerez, the so-called Sherry Triangle, have been suffering over recent years. You only have to offer a glass of good Oloroso to any wine drinker under sixty years old for a rejection to come your way, with often-repeated excuses: “I’m sorry, Sherry gives me a headache”; “I’ve not eaten yet”; “I’d rather have a beer”...

As a lover of Spanish, nothing hurts me more than the contempt that wines from the Marco de Jerez, the so-called Sherry Triangle, have been suffering over recent years. You only have to offer a glass of good Oloroso to any wine drinker under sixty years old for a rejection to come your way, with often-repeated excuses: “I’m sorry, Sherry gives me a headache”; “I’ve not eaten yet”; “I’d rather have a beer”...

The impoverished offering of Sherries, or fortified wines, on restaurant wine lists is another indication confirming the sad reality: the new generations of consumers have turned their backs on the wines from the Jerez demarcation.

Therefore, some serious thinking is required to understand what has happened for such historic wines, much sought-after by vast numbers, to become the ugly ducklings of Spanish viticulture. And, as it turns out, various conclusions can be drawn: on the one hand, aperitif wines have lost their place in the vertiginous modern world (who has time for an aperitif in our hectic everyday life?); on the other, society’s tastes have changed, to such an extent that Sherry is associated with bygone Spain, which is just what happened with brandy too.

However convincing these arguments are, as far as I’m concerned, I prefer not to fall in with this line of thinking and rise up against the injustice, taking advantage of this article to make a stand in support of Sherry wines. I’ll say it loud and clear: I think they are the real treasure-trove of Spanish viticulture, with a unique and inimitable character.

However convincing these arguments are, as far as I’m concerned, I prefer not to fall in with this line of thinking and rise up against the injustice, taking advantage of this article to make a stand in support of Sherry wines. I’ll say it loud and clear: I think they are the real treasure-trove of Spanish viticulture, with a unique and inimitable character.

I think Sherry wines are the real treasure-trove of Spanish viticulture, with a unique and inimitable character.

This uniqueness occurs for several reasons. One of which is, of course, the singularity of the limy soils where these vineyards grow, especially on Jerez’s most renowned estates, such as the legendary Macharnudo.

A second reason is the extreme weather conditions, with the stifling heat hardly alleviated by the winds that blow from the nearby Atlantic.

The third is the varietal selection, which has remained unchanged since time immemorial: the Palomino is predominant in Jerez; the Muscatel in Malaga; and the Pedro Ximenez in Montilla-Moriles (Cordoba).

Jesús Barquín, one of the greatest experts on Andalucian winesAlthough, perhaps the reason carrying most weight may be/is the wine-making methods and ageing, based on the solera and criadera system: Andalucia’s greatest contribution to the history of the Human Race. Thanks to these methods, each bodega’s foreman can regulate the influence of the temperature and draughts of air without having recourse to technology-based methods. These wise professionals display all their know how in ageing halls, some as vast and lugubrious as cathedrals, where the yeasts find suitable conditions for developing and taking a decisive role in the wines that undergo biological ageing (Finos and Manzanillos). It is there too where the wines experiencing oxidative ageing (Olorosos, Palo Cortados, Amontillados, etc.) take on their marvellous character, capable of ageing gracefully almost forever.

Jesús Barquín, one of the greatest experts on Andalucian winesAlthough, perhaps the reason carrying most weight may be/is the wine-making methods and ageing, based on the solera and criadera system: Andalucia’s greatest contribution to the history of the Human Race. Thanks to these methods, each bodega’s foreman can regulate the influence of the temperature and draughts of air without having recourse to technology-based methods. These wise professionals display all their know how in ageing halls, some as vast and lugubrious as cathedrals, where the yeasts find suitable conditions for developing and taking a decisive role in the wines that undergo biological ageing (Finos and Manzanillos). It is there too where the wines experiencing oxidative ageing (Olorosos, Palo Cortados, Amontillados, etc.) take on their marvellous character, capable of ageing gracefully almost forever.

Luckily, more recently I have felt less alone in my Numantine defence of wines from the Jerez region. There are others too who have put up a fight against the indifference, driving forward projects which make a contribution to recouping the image of Sherry as a real luxury product and not a quaint fairground souvenir.

Macharnudo Alto Estate The most audacious stance in this respect is that taken by Equipo Navazos, which started up as a club of wine enthusiasts dedicated to selecting the region’s most delicious rare finds for their own consumption, but they have gradually found a market for their precious wares in restaurants too: antiquated Manzanillas, Finos with extra-long ageing, archaic Amontillados and other gems that were lying dormant in the remotest corners of several bodegas. You couldn’t expect less from a team led by Jesús Barquín, undoubtedly one of the greatest experts on Andalucian wines.

Macharnudo Alto Estate The most audacious stance in this respect is that taken by Equipo Navazos, which started up as a club of wine enthusiasts dedicated to selecting the region’s most delicious rare finds for their own consumption, but they have gradually found a market for their precious wares in restaurants too: antiquated Manzanillas, Finos with extra-long ageing, archaic Amontillados and other gems that were lying dormant in the remotest corners of several bodegas. You couldn’t expect less from a team led by Jesús Barquín, undoubtedly one of the greatest experts on Andalucian wines.

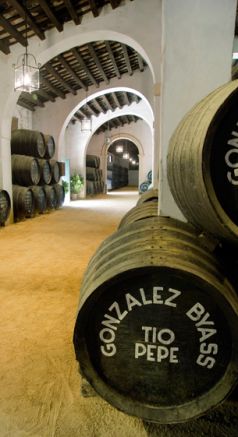

Although Jerez errs on the side of being a wine-growing region suffering from considerable immobility, some wineries are showing signs of intelligent life. The upshot is that recently interesting initiatives have been put forward too in the depths of the old bodegas. The case of González Byass is a good example, since despite being bound up for a long time with producing one of the region’s best-sellers – the very same Tío Pepe – it is not resting on its laurels and now and again it pulls out of the hat some gem that contributes to its own prestige and the DO’s in general. The last one has been the Palmas collection of Finos, comprising three remarkable Finos and an Amontillado, which represent the true essence of Tío Pepe’s character. Top-notch wines, every one of them, that are well worth applauding.

Interior of Gonzalez Byass´s winerySmaller wineries too are doing their bit for restoring Jerez’s prestige, such as Emilio Hidalgo, which for some years now has opted for offering more sublime and mature versions of the Sherry wine type. Their mainstay is La Panesa, a Fino, impressive from its very presentation to its last drop. Nothing at all to do with fairground Finos, needless to say.

Interior of Gonzalez Byass´s winerySmaller wineries too are doing their bit for restoring Jerez’s prestige, such as Emilio Hidalgo, which for some years now has opted for offering more sublime and mature versions of the Sherry wine type. Their mainstay is La Panesa, a Fino, impressive from its very presentation to its last drop. Nothing at all to do with fairground Finos, needless to say.

Finally, it would not be fair to end this analysis without taking into consideration the project run by Bodegas Tradición, one of the few of a new breed that have managed to get established in a region where new ventures are practically impossible. But they have been even more daring, since Tradición is dedicated exclusively to old wines, with an exclusive range that includes an Amontillado, a Palo Cortado and an Oloroso VORS (Vinum Optimum Rare Signatum, or Very Old Rare Sherry with over 30 years of ageing) and a slightly younger PX (VOS, aged for more than 20 years). They are all majestic, complex and singular wines. They are the distinctive hallmarks of Tradición, which meant a major investment for a production run not exceeding 12,000 bottles a year. That’s definitely what it is to love Sherry!